Without Mugabe, is democracy coming to Zimbabwe? Probably not.

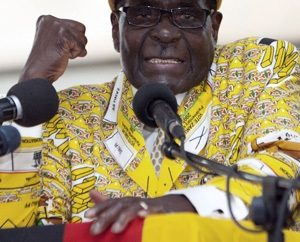

On Tuesday, after 37 years of authoritarian rule, Robert Mugabe resigned as president of Zimbabwe. That stunning move — celebrated by lawmakers cheering and citizens dancing in the streets — came after a dizzying series of events. Mugabe’s two most-likely successors — his wife, Grace Mugabe, and Vice President Emmerson Mnangagwa — had been jockeying for power. The president had Mnangagwa fired, provoking his allies in the army to seize power. Stripped of his party leadership and threatened with impeachment, Mugabe finally resigned.

But is Mugabe’s overthrow really a step toward democracy, as Zimbabweans and international observers alike are suggesting? Although there are reasons to think so, as I’ll explain below, Zimbabwe without Mugabe is probably heading not toward democracy but merely toward a different autocrat.

Coups can sometimes lead to democracy

The British foreign secretary has called the crisis a “moment of hope.” The State Department expressed its desire for a “new era” in Zimbabwe. Within the country, some citizens proclaimed a “second independence day.” The opposition party, the MDC, has called for democratization. Even some members of the ruling ZANU-PF party, which has ostensibly governed the country for decades, are reportedly wearing T-shirts reading “new era/Team ZANU-PF.”

It’s true that coups can remove repressive dictators, sometimes resulting in elections and even real democratization. A 2014 coup in Burkina Faso unseated Blaise Compaoré, who had ruled since 1987, resulting in free and fair elections — the first in that country to constitutionally transfer power to a new president.

[To understand the coup in Zimbabwe, you need to know more about Grace Mugabe]

Further, on Saturday, tens of thousands of Zimbabweans took to the streets to celebrate a post-Mugabe era. The military may have inadvertently released popular pressure for liberalization that it will not be able to control, especially because Zimbabweans oppose military rule by an overwhelming margin of 69 percent to 31 percent, according to a 2017 Afrobarometer survey. Even ZANU-PF insiders are proclaiming their desire to amend the constitution and decrease the powers of the presidency.

But democracy is an unlikely outcome for these reasons

A look at both broad African political trends and at the specifics of Zimbabwean politics suggests that there are many stumbling blocks between Mugabe’s ouster and open elections.

African trends. Fifteen coups toppled African regimes between 2000 and 2012. Only five resulted in elections that transferred power to civilians. Of those, only Niger’s government lasted more than four years without being overthrown by another coup. Those are long odds.

Zimbabwe’s military is loyal to ZANU-PF. But Zimbabwe’s history of military involvement in politics is still more significant. After independence but before the 1980 transition to majority rule, the country was in turmoil, with two rebel groups — ZANU and ZAPU — at war with the old Rhodesian state security services. While ZANU recruited from the Shona ethnic group, ZAPU drew members mostly from the Ndebele.

During the transition, the British worked to help integrate the three entities into one professional army. That fell apart in 1982, however, when Mugabe — the ZANU leader and new Zimbabwean president — used a specially trained brigade of fellow Shona to massacre Ndbele civilians and persecute former ZAPU soldiers, driving them from the military. After, Mugabe consolidated his power under the renamed ZANU-PF, backed by a personally and ethnically loyal army of former guerrilla comrades.

In 2001, however, it looked as though Mugabe would not be reelected. The commanders of the army, air force and police, along with several intelligence directors, conducted a televised news conference in which they announced their loyalty to ZANU-PF and threatened to intercede if Mugabe did not win. The security services also routinely suppressed the opposition and intimidated voters. After Mugabe lost the first round of the 2008 presidential elections, they unleashed a campaign of violence that ultimately led the opposition candidate, Morgan Tsvangirai, to withdraw. Mugabe secured victory unopposed.

The military has continued to be the enforcement arm of ZANU-PF’s power, all the way down the ranks. Officers are expected to be loyal ZANU-PF party members in exchange for patronage. As Mugabe dispossessed white farmers, beginning in 2000, military officers were rewarded with land grants. Across ranks, party loyalty is necessary for promotion. Suspicions of siding with the opposition frequently led to punishment and demotion.

Although the military may have unseated one party leader, there’s no reason to believe it has shed its political loyalties. It is widely believed that the generals will not tolerate a ZANU-PF loss at the polls. Without real political competition, and secure in its military backing, ZANU-PF has little incentive to reform.

It’s notable that the army unseated Mugabe only when his administration had cast aside the military’s preferred successor — suggesting that this coup is not fundamentally about democracy.

Mnangagwa is unlikely to lead liberalization. He has long served as the key link between the army, the intelligence apparatus and the ZANU-PF party organization. He has been Mugabe’s right-hand man for much of the past 37 years, often responsible for conducting his dirty work. Mnangagwa was the national security minister and led the Central Intelligence Organization during the 1980s crackdown called Gukurahundi, which killed an estimated 20,000 civilians in Matabeleland. Allegedly, he also orchestrated the campaigns of electoral repression and violence that occurred between 2000 and 2008.

In other words, the military’s candidate for Mugabe’s seat is deeply implicated in the corruption and human rights abuses of the Mugabe regime.

The military and ZANU-PF have coordinated on their preferred new president, Mnangagwa, who is likely to sweep to electoral victory next summer through continuing voter repression. Neither Mnangagwa nor the military nor ZANU-PF are likely to redress their past wrongs, promote meaningful change, allow real electoral competition, or desist from future violence.

There is a small chance for a new era — if the public has become too mobilized and engaged to be easily silenced again. That could create real pressure for change.

Kristen A. Harkness is a lecturer on international relations at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland and author of “When Soldiers Rebel: Ethnic Armies and Political Instability in Africa,” forthcoming from Cambridge University Press. Her data on African coups and electoral transfers of power are available upon request.